Freedom of Panorama

Freedom of Panorama (FoP) (English Wikipedia article on FoP/Wikimedia Commons policy page on FoP) refers to a limitation or exception to copyright. It can be defined as:

- "The legal right in some countries to publish pictures of artworks, sculptures, paintings, buildings or monuments that are in public spaces, even when they are still under copyright." (Dulong de Rosnay and Langlais, 2017)[1]

- "An exception under copyright laws, similar to fair use, that dispenses with the need to secure prior permission from a copyright owner for the use of a work." _ Atty. Chuck Valerio of the Philippines' IPOPHL as quoted by Reyes (2021)[2]

Importance[edit]

| “ |

There are only a few forces stronger in the world than the desire of people to express and share their experiences and thoughts, in writing, image or song. We preserve our journeys and curate our impressions for long winter nights and entire generations to come. Our laws are seeking to reward the author, encourage the creation and ensure the exchange of works. When interests overlap, they provide guidance for mediation. Freedom of Panorama is the codified acknowledgment that a public sphere truly exists for everybody's benefit. A building or sculpture deserves and receives the protection of the law, yet the reach of that protection ends where the protection of the public sphere begins. In order for copyright to work and to be accepted, it has to do more than just protect works. It must provide breathing space for those who express, who portray, who sculpt, who quote or who criticise. Freedom of Panorama is part of this breathing space to those who create, to Europe's over 500 million authors. |

” |

— Felix Reda (2015)[3] | ||

Freedom of Panorama (FoP) is very important for Wikimedia projects, because it permits Wikimedia Commons – the media file repository site of Wikimedia Foundation – to freely host images (like Wikimedians' photos) of more recent/potentially-copyrighted works of architecture and public art found in and/or visible at public spaces and/or premises open to the public under permitted free culture licenses. Such images are being used on Wikipedia (various language editions), Wikivoyage, and other projects. On Wikipedia, images are used to illustrate articles on architecture and public art, as well as lists of buildings and monuments/statues.

Wikimedia Commons has a very strict licensing policy anchored on the Principle of Free Cultural Works. Under this principle, the following conditions must be applicable: the freedom to use and perform the work, the freedom to study the work and apply the information, the freedom to redistribute copies, and the freedom to distribute derivative works.

- Regarding architectural FoP

- When architectural FoP was introduced in the United States in 1990 coinciding with giving U.S. buildings copyright protections:

Motivation for the exemption stems from the key role that architectural works play in a citizen’s daily life, not only as a form of shelter or investment, but as a work of art with a very public and social purpose. Congress also reasoned that exempting pictorial representations of architectural works would not interfere with the normal exploitation of architectural works because of the nature in which the pictorial representations are used. For example, millions of people visit cities every year and take back photographs, posters, and other pictorial representations of architectural works as mementos of their trip. Architectural photographs are also often essential bases of scholarly books on architecture. Given the important public purpose and the lack of harm to the copyright owner’s market, Congress decided to provide the exemption, rather than relying on the doctrine of fair use.

- Architectural FoP is vital for a vibrant and conducive discourse on architecture. Per Rory Stott of Archify: "But most importantly for architects, we live in a world where images of our built environment - shared freely between people via the internet - are increasingly important in constructing a discourse around that built environment. We live in a world that requires freedom of panorama in order for architects to make the world a better place. And architects should be pretty upset about how many restrictions have been placed, and continue to be placed, on that freedom."[4]

- Conclusion of Images of Public Places: Extending the Copyright Exemption for Pictorial Representations of Architectural Works to Other Copyrighted Works, a 2005 article by Andrew Inesi

Technological changes are empowering consumers to use photographs in ways once reserved to professionals. However, these same technologies make it more likely that consumers will come into conflict with copyright owners whose works are incorporated in their images. This conflict is especially likely with respect to photographs of public places, many of which inevitably include third-party copyrighted works.

Copyright law is ill-equipped to handle these changed circumstances. In particular, the de minimis and fair use tests, which in the past have served as bulwarks against unreasonable application of copyright, are not well-suited to this task today. In most courts de minimis does not apply to the vast majority of public photography uses. Fair use's greatest weakness – uncertainty – is becoming a more significant liability in an age where image uses are no longer easily classified and image users are less likely to be legally sophisticated.

Photographs of architectural works as a model, Congress should exempt from copyright all uses of photographic representations of copyrighted items ordinarily visible in public places. The benefits of such a change would be great, and the costs minimal. Moreover, this change would create a simple, easily-understood rule that is well-suited to the needs of consumers.[5]

Implications of lack of Freedom of Panorama[edit]

On-wiki implications[edit]

- Deletion requests on Wikimedia Commons: see c:Category:FOP-related deletion requests. An analysis conducted by a team within Wikimedia in July–August 2023 revealed that FoP-related deletion requests make up the majority factor behind the perennial deletion backlogs the Wikimedia Commons admins regularly face.

- Deletions on English Wikipedia: w:User:JWilz12345/Deleted no FOP (list created by User:JWilz12345, anyone can freely edit or contribute)

- DMCA takedowns:

- Inadequate Wiki Loves Monuments coverage of a country's built heritage (which should be all buildings + sculptural monuments). Both Bulgaria and Greece do not permit commercial form of FoP, forcing Wikimedians in both countries to come up with lists excluding all newer public monuments everytime they participate, thus limiting the coverage of the photo competition in both countries.[6] In several other countries with no FoP (as of 2022), like Afghanistan, Argentina, Ghana, and the Philippines, this legal barrier affects the motivations of Wikimedia chapters and local groups in those countries to undertake their editions of WLM competitions as well as participation rates.[7]

-

Denmark (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments)

Denmark (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments) -

Denmark (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments)

Denmark (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments) -

Japan (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments)

Japan (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments) -

Taiwan (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments)

Taiwan (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments) -

United States (for no FoP on non-architectural monuments)

United States (for no FoP on non-architectural monuments) -

United States (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments)

United States (for insufficient FoP on non-architectural monuments)

More censored images at c:Category:Censored by lack of FOP (and its subcategories).

Off-wiki implications[edit]

- Case of Portlandia

- Second-largest copper-hammered statue in the U.S. (after New York's Statue of Liberty), located in Portland, Oregon.

- No national icon recognition unlike the Lady Liberty: absent in post cards or souvenir photographs, due to copyright enforcement by its author, sculptor Raymond Kaskey.

- Supporting such restrictions is Peggy Kendellen of the Regional Arts & Culture Council: "Many artists have had their works taken advantage of in the past....It's important to protect the rights of the artist."

- Opposing such restrictions are Chris Haberman, an artist himself (a muralist) and co-owner of the Peoples Art of Portland gallery, and Kohel Haver, a local copyright lawyer representing artists:

- "Public art should be in the public domain." _ muralist Chris Haberman

- "It is unfair to have a situation where artists are afraid to make a painting of a statue or include public art in the background, or members of the public are afraid to take photos with the statue and post them on Instagram. The [city] didn't realize it was giving away the rights to an icon." _ lawyer Kohel Haver

Some critics of Freedom of Panorama[edit]

- ADAGP (Société des Auteurs Dans Les Arts Graphiques et Plastiques): based in France, a vocal critic of Wikipedia community and other online platforms in terms of using works permanently found in public, as shown in their opposition to the attempt by FoP advocates of making FoP mandatory throughout the European Union in 2015. In their presentation, ADAGP questioned why Wikimedians didn't choose to use what they call as more respected CC-BY-NC-ND (non-commercial license) instead of the CC-BY-SA license that for them is "inacceptable for the authors"; they also claimed Facebook, Twitter (now X), Instagram, Flickr, and Pinterest must pay to the authors of public space works. ADAGP appears to be critical on Wikipedia's continued hosting of French architecture, giving five examples of French buildings that Wikipedia users must seek authorization from the works' architects: European Parliament building, La Grande Motte, Stade de France, Bibliothèque nationale de France, and L'Institut du Monde arabe. (presentation of ADAGP to the EU Parliament). ADAGP in 2012 sent a cease-and-desist letter to the administrators of French Wikipedia, to take down an image of an illegal graffiti in France (w:fr:Wikipédia:Legifer/mars 2012#Image de graffiti et ADAGP).

- Arts Law Center of Australia: criticizes Australian FoP for public art (sculptures and artistic craftsmanship works). (2006 article, 2013 article)

- South African Institute of Intellectual Property Law: opposes the introduction of FoP in South Africa, claiming it allows "unlimited use of re-uses of artistic works in public places." For this statement as well as Wikipedia's response, see page 30 of the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition's Responses to public submissions to the Select Committee on Trade and Industry Economic Development, Small Business Development, Tourism, Employment and Labour: On the Remitted Bills, dated April 18, 2023.

Situation around the world[edit]

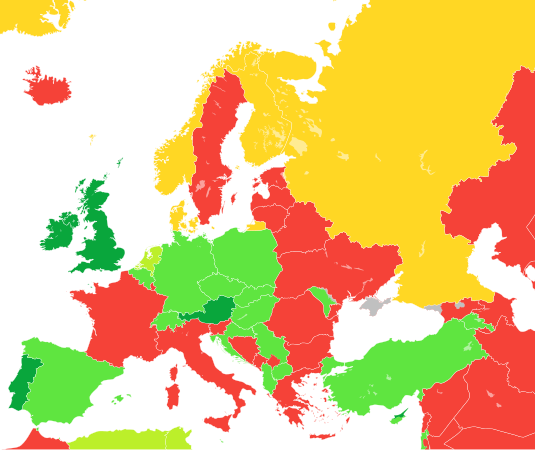

The varying copyright law provisions of more or less 200+ countries around the world mean uneven FoP statuses. This is reflected in the world map and regional maps detailing FoP statuses below.

-

FoP statuses in Europe

-

FoP statuses in Southeast Asia

The long-term solution: introduction of suitable FoP legal right in countries that still do not provide such.

A close call: 1986 WIPO-UNESCO proposal for global architectural FoP[edit]

Jane C. Ginsburg of the Columbia Law School mentions of some meetings between WIPO and UNESCO in 1986, in her 1990 study. The meetings aimed at "seeking to elaborate general principles of copyright law for works of architecture." A finalized proposal (cited as "Principle WA. 7, 22 COPYRIGHT 401, 411 (Dec. 1986).") read: "The reproduction of the external image of a work of architecture by means of photography, cinematography, painting, sculpture, drawing or similar methods should not require the authorization of the author if it is done for private purposes or, even if it is done for commercial purposes, where the work of architecture stands in a public street, road, square or other place normally accessible to the public."[10]

The default rule would have been private uses only, and commercial use would have been permitted if the building is permanently installed in public spaces. In both cases, users' images should only show exterior architecture.

For some reason, this finalized wording is not existing in the current text of the treaty.

Initiatives and areas of Discussion[edit]

The following are some pages discussing or referencing FoP

- Pilipinas Panorama Community

- Pilipinas Panorama Community – Philippine initiative

- Pilipinas Panorama Community – Discussion

- Wikilegal pages

- Wikilegal/Copyright of Images of Memorials in the US

- Wikilegal/FOP statues

- Wikilegal/Pictorial Representations Architectural Works

- Other pages in Meta-wiki

- Freedom of Panorama in Europe in 2015

- Wikimedia South Africa/Copyright Amendment Bill#Freedom of Panorama – South African initiative

- Wikimedia Community Zambia/Freedom of Panorama – Zambian initiative

- At Wikimedia Commons

- c:Commons:Freedom of panorama campaign (now considered defunct)

- c:Commons:Requests for comment/Non-US Freedom of Panorama under US copyright law – on the possible interference of the U.S. copyright law (that does not provide FoP to sculptural monuments) over images of monuments from countries that have valid FoP for sculptural monuments (e.g. U.K., Germany, Netherlands, Poland, Hungary, Malaysia, Singapore, India, Australia, Uganda...); current consensus is to slap all images of monuments of the said countries with c:Template:Not-free-US-FOP template to warn readers and reusers living or based in the United States of restricted image use due to the U.S. copyright law that the U.S. courts may lean

- On YouTube

- Katherine Maher: The Monkey Selfie, Public Domain, Freedom of Panorama, The EU Copyright Directive – Walled Culture – at 11:30 ("Katherine explains the issue of freedom of panorama, with the Eiffel Tower's light show and the Brussels Atomium as examples, and observes that the EU copyright Directive didn't turn out as hoped.")

- At FoP-related pages by affiliates

- Filming and taking photos in public places: an explainer – Wikimedia Australia (regarding Australian FoP)

In progress FoP introduction moves[edit]

- South Africa

The Copyright Amendment Bill was passed by the National Council of Provinces (NCOP); 7 out of 9 provinces in favor. As of September 2023, sent to the National Assembly plenary for re-approval.

See also: Wikimedia South Africa/Copyright Amendment Bill/Timeline

- Philippines

Seven bills in the lower House of Representatives (HoR) and six bills in the upper Senate seeking to amend/modernize Republic Act 8293 (Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines).

The ones with FoP provision, House Bills 799, 2672, and 3838, as well as Senate Bill 2326, remain pending as of this writing (2024-01-28). Passed in HoR and awaiting Senate approval is House Bill 7600, which does not have FoP and is more focused on giving increased powers to the country's copyright office and combating piracy, in real world and online.

See also: Pilipinas Panorama Community/Freedom of Panorama/Progress

Successful FoP introductions[edit]

Note, since the establishment of Wikimedia Commons in 2004

- Moldova: 2010, complete outdoor FoP aligned to EU standards (source: English Wikipedia article "Freedom of panorama")

- Armenia: April 2013, complete FoP except interiors. See c:Commons talk:Freedom of panorama/Archive 12#FoP in Armenia

- Russia: October 2014, partial only for architectural and landscape art works only, see Free licenses and freedom of panorama now recognized in Russian law! by Diff blog

- Albania: in 2016, complete FoP except interiors. See c:Commons talk:Freedom of panorama/Archive 16#Updated Albanian FOP according to the new Copyright Law and Others Right relatad.

- Belgium: July 2016, complete FoP (except public interiors), see this information page and this press release by Wikimedia Belgium. See also these two Commons discussion areas: at Village Pump proper and at copyright tab of the Village Pump.

- Timor-Leste: May 2023, coinciding with the effectivity of the country's first-ever copyright law, the Code of Copyright and Related Rights, and appears to lean towards the Portuguese model; see also c:Commons talk:Copyright rules by territory/East Timor#New copyright terms.

Notable removals or abolitions of FoP[edit]

- Costa Rica - in 2006, changed to non-commercial use only, part of amendments to comply with the Central America–Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), see this* (same discussion)

- Guatemala - in 2006, changed to personal use only, CAFTA-DR reason* (same discussion)

- Honduras - in 2006, changed to personal use only, CAFTA-DR reason* (same discussion)

- Seychelles - in August 2014, see this

- Eswatini - in 2018, see this

- Kiribati - in November 2018, see this

- Myanmar - in 2019, see this

- Vietnam - in January 2023, changed to non-commercial only, refer to this discussion.

- Nigeria - in March 2023, changed to use in audio-visual and broadcast media only, see this discussion

Countries to watch out[edit]

![]() Note: Countries that Wikimedians need to be vigilant.

Note: Countries that Wikimedians need to be vigilant.

- Australia - criticism to Australian FoP, especially the provision related to sculptures and works of artistic craftsmanship (Section 65): article1, article2

- Chile - a proposal in early 2024 seeks to limit FoP; sharing and distribution – with lucrative or profit-making intent – of any images of copyrighted artistic works permanently found in public spaces require remunerations to the artists who made those works; this will gravely affect Spanish Wikipedia's ability to illustrate articles of Chilean monuments and buildings. (source1, source2, from the website of Wikimedia Chile)

- Sweden - public consultation on major reforms of the Swedish copyright law in the midst of Internet age was held in early 2024. Per the relevant summary (regarding FoP) of the discussions (pages 27–28), FoP is going to be expanded to also include monumental works inside tunnels, but will be "narrowed in relation to what currently applies in that use of a reproduction where the work constitutes a central theme is not included if it takes place for commercial purposes." The restriction on commercial uses or financial gain is proposed to be implemented on the part of FoP concerning public monuments and art; commercial uses of works of architecture remain unaffected. (document of the public consultation; discussion on Wikimedia Commons)

See also[edit]

- Reform of copyright and copyright-related protections

- Copyright Repository

- User:JWilz12345/FOP/Global statuses (User:JWilz12345's summary table of FoP statuses globally)

References[edit]

- ↑ Dulong de Rosnay, Mélanie; Langlais, Pierre-Carl (2017). "Public artworks and the freedom of panorama controversy: a case of Wikimedia influence". Internet Policy Review.

- ↑ Reyes, Mary Ann LL. (2021-11-28). "Changing landscape of copyright". The Philippine Star.

- ↑ "Debate: should the freedom of panorama be introduced all over the EU?". European Parliament. 2015-07-02.

- ↑ Stott, Rory (2016-04-07). "Freedom of Panorama: The Internet Copyright Law that Should Have Architects Up in Arms". Archify.

- ↑ Inesi, Andrew (2005). "Images of Public Places: Extending the Copyright Exemption for Pictorial Representations of Architectural Works to Other Copyrighted Works". Journal of Intellectual Property Law (University of Georgia School of Law) 13 (1): 101. Retrieved 2024-02-16.

- ↑ Lodewijk (2016-10-18). "Cultural Heritage Laws & Freedom of Panorama". Wiki Loves Monuments.

- ↑ c:Commons:Wiki Loves Monuments/DEI research 2022/Interim report#Primary Research

- ↑ Locanthi, John (2014-09-09). "So Sue Us: Why the Portlandia Statue Failed to Become an Icon". Willamette Week.

- ↑ Cushing, Tim (2014-09-12). "Sculptor Says 'Capitalism' Drives His Aggressive Enforcement Of Rights To Publicly-Funded 'Portlandia' Statue". Techdirt.

- ↑ Ginsberg, Jane C. (1990). "Copyright in the 101st Congress: Commentary on the Visual Artists Rights Act and the Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act of 1990". Scholarship Archive (Columbia Law School) 14: 496. Retrieved 2024-02-16.